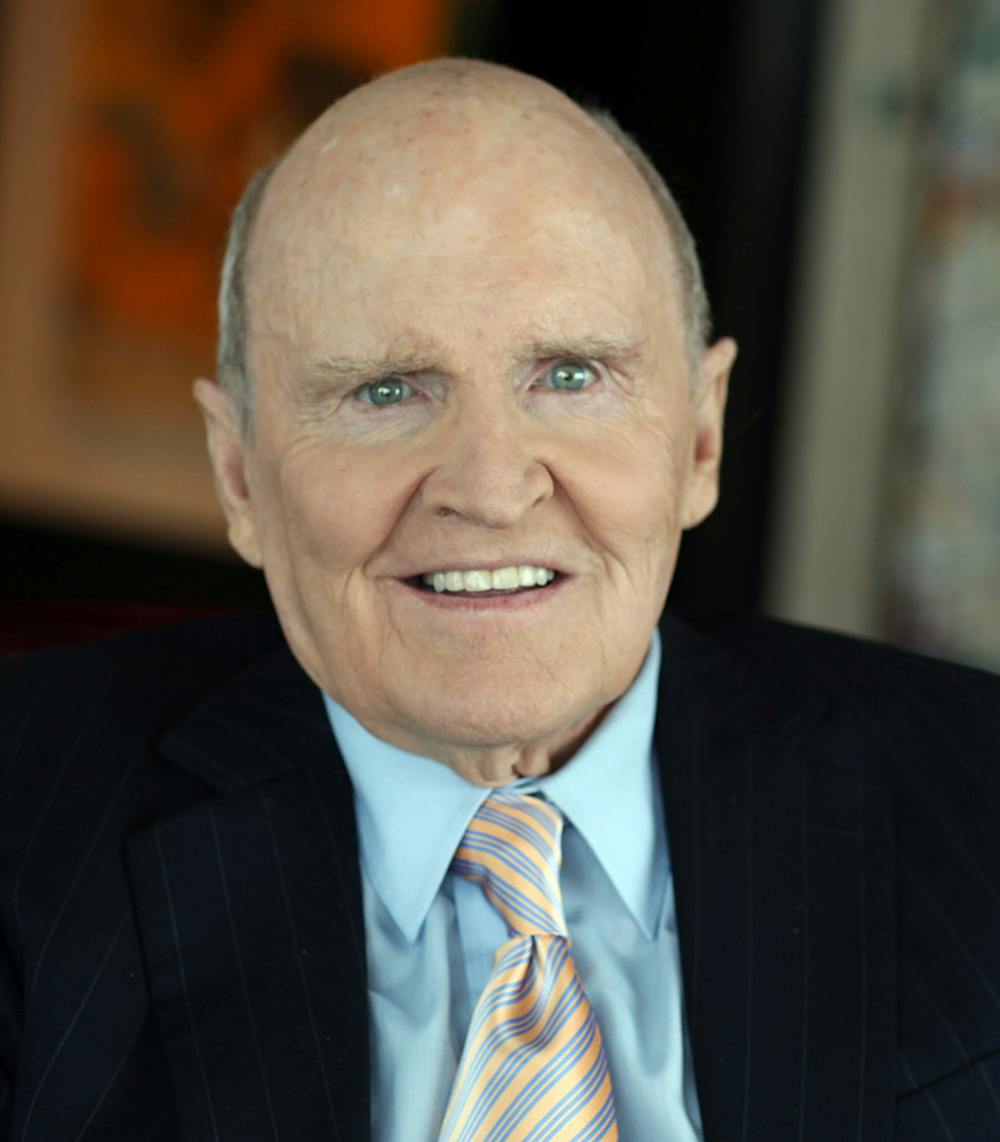

In 1981, Jack Welch was appointed CEO of General Electric. In just five years, Welch laid off more than 100,000 workers, according to Business Insider. Before Welch’s appointment, GE developed light bulbs, jet engines and power systems; however, within a few years of Welch’s position, many of these projects were outsourced or ended. Despite this, Welch led the company to become the most valuable corporation in the world by 1997. He turned layoffs into a sign of strong leadership and spread this strategy to each subsequent acquisition.

The deterioration of human capital and the lack of program development made this value purely based on perception. The constant acquisitions made the stock price go up, padding Welch’s portfolio. However, when the glorified finance company faced the 2008 financial crisis, it was unable to maintain its weight. In 2018, the organization was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average after over 100 years of membership.

Welch’s approach was not an isolated event. Several changes in fiscal and regulatory policy allowed his strategy to spread like wildfire. This is commonly known today as “Financialization.” Executives and board members are not rewarded for expanding company infrastructure or product quality; they are rewarded through the constant expansion of shareholder value.

The most significant evidence of this is the changes in the average Price-to-Earnings ratio within the S&P 500. Starting in 1950, through company earnings, it would take an investor roughly seven years to make back the money invested in the S&P 500. However, as of December 2025, it takes an investor roughly 29 to 30 years.

Though PE ratios can increase for many reasons, their inflation shows share prices far surpassing the company’s earnings potential. The expansion reflects organizational leaders being compensated for share value spikes, not the long-term health of the company. Thus, the business model of constant acquisition and then stripping for parts takes precedence over developing human capital and research.

This strategy was not created in a vacuum. In 1982, the SEC created a safe pathway for organizations to engage in stock buybacks free from accusations of market manipulation. Before this change, stock buybacks were looked at with scrutiny, causing possible investigations into the company for manipulating its stock price. Once stock buybacks were normalized, executives were given a pathway to both inflate shareholder value while also padding their own portfolios.

Additionally, the massive reductions in corporate tax rates allowed organizations to hold more after-tax capital to engage in stock buybacks. In the 1960s, the highest corporate tax rate was 52.8%. This was eventually reduced to 21% as of 2024, and the highest tax bracket was significantly increased, according to the Tax Policy Center. When corporations were subject to higher tax rates, they were incentivized to reinvest profits back into the organization. These investments were often considered expenses and thus were not taxable. Thus, employee benefits were improved, and greater importance was given to research. However, when tax rates are reduced, companies have access to a larger percentage of their earnings to engage in stock buy-backs, making them take precedence over reinvestment.

The “Financialization” of America was not something that happened overnight. It consisted of dozens of changes in fiscal policy as well as American culture that gave way to an extremely dominant stock market and finance industry. This came at the expense of domestic manufacturing, product development and employee benefits.

The Slate welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.